Before I knew how to hold a book, I learned to hold space for stories.

Oral Story telling as a gateway to literacy

Growing up in rural South Africa, my early years were devoid of television, books, and the internet—not by choice, but by circumstance. For my family, these luxuries were neither available nor accessible. Yet, in that absence, something far richer took root: the ancient tradition of oral storytelling.

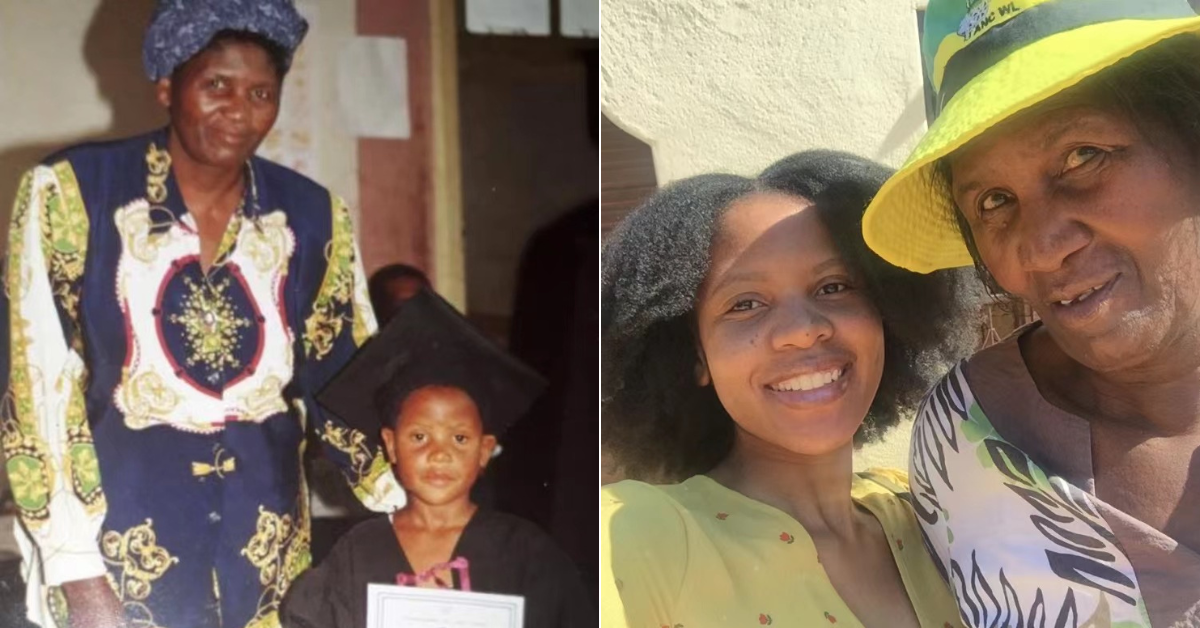

Before I turned six, our evenings followed a sacred rhythm. As the sun dipped below the horizon, my family would gather outside around a crackling fire. There, under a blanket of stars, my grandmother and great-grandmother would weave folktales known as Mintsheketo. Each tale was more than entertainment; it was a ritual of community, a thread stitching us together across generations.

Every story began with the same invocation:

“Garingani-wa-Garingani.”

(Storyteller, child of the storyteller.)

To me, these words were an ode—a tribute to the ancestors who had passed down these narratives like heirlooms. In unison, we’d respond: “Garingani.” It was a vow, a way to honor those who came before and those who would follow. Then, the magic began:

“Khale ka khaleni a ku ri na…”

(Long, long ago, there was a…)

The tales that followed were thrilling, whimsical, and steeped in wisdom. They transported us to worlds where animals spoke, heroes outwitted villains, and ordinary people performed extraordinary deeds. Every story ended with a moral—a seed of guidance—and a collective wish, as if the embers of the fire carried our hopes into the night.

Those moments did more than spark my imagination; they taught me that stories are alive. They breathe in the spaces between teller and listener, binding communities and bridging time.

As I grew older, my hunger for stories outgrew the tales my grandmothers could recount. I craved more—more worlds, more voices, more lessons. That hunger led me to books. The first time I held a story in my hands, I realized: This is Garingani-wa-Garingani too. The pages were a new fire, and every sentence kept the ancestors’ voices alive.

The death of oral storytelling, effects on literacy

By the time my younger sister was born, technology had reshaped our lives. The firelit circles were replaced by the glow of TV soap operas. The ritual of call-and-response faded into passive consumption. I sometimes wonder if this shift is why her generation sees stories differently—not as communal treasures to be shared, but as fleeting distractions to be consumed.

But I know the truth: Stories never lose their power. They simply change form.

Today, when I open a book, I still whisper “Garingani” under my breath. It’s my way of remembering—the fire, the voices, the hands that held mine as the night stretched on. And though the world moves forward, some things remain:

We are still the children of storytellers.

And every story is a homecoming.